Sin categoría

DaVinci Resolve Fusion 16 + Fusion Studio 16, two sides of the same coin? – PART 1

INTRODUCTION (or the Blues of a VFX Operator)

Fusion is a very veteran application in the world of VFX; created in 1987 as an in-house tool for a studio, it was marketed a decade later by Eyeon Software. We are therefore in a similar situation to Resolve and Fairlight: applications with a long professional history but of little popularity until their acquisition by BMD.

I first heard about Fusion back in 2003-4, when I was hesitating between learning it or Shake (v2.5) as a strategy to improve my compositing skills after many hours with After Effects. The big advantage of Fusion was that back then it accepted the native AE plugins that I was already used to (not anymore) and its biggest drawback was that it only ran on windows and I was already using Final Cut, so leaving Mac was a difficult jump for me.

I finally opted for Shake (R.I.P) after its purchase by Apple, thinking that with that backing I could be reassured about its continuity (big mistake) which was important after the hours of study and desperation it would take me to learn the mysterious paradigm of nodal composition.

The story in a nutshell: Apple felt that Shake would be great for Hollywood post production studios but with an ugly interface and a hellish learning curve for the average Mac user, it didn’t sell machines and after killing it they brought Apple Motion into the world. In Apple’s defense, I can attest that having taught Shake classes 90% of the students fled in terror to the maternal arms of that Photoshop with timeline that was After Effects…

As for Fusion, over the next few years, I would hear from small studios, outside the paradigm of the big VFX companies in Spain, that they were using it for such and such a series (Los protegidos) or such and such a movie (La piel de la tierra). The program, although it never came close to the VFX throne conquered by Nuke, had its great apologists in small studios and some concentration in diverse geographic locations (Russia, India, Germany).

Talking to people from those studios that had adopted Fusion in Spain I remember they told me that they were happy with the program but had three problems: lack of operators, lack of prestige/recognition among clients and the scarce training available; Fusion was therefore an extravagant bet if we compare it with other consolidated programs in the market at that time such as Combustion (R.I.P), Autodesk Smoke (R.I.P) or Quantel eQ (R.I.P).

Eventually I followed my steps as a free-lance operator with a program that seemed to unite my three usual fields of work: editing, color and VFX (again being able to work with nodal system, yes!!!!!) . That program was Avid DS (R.I.P again and already van….) and at the time it seemed to me that it was the perfect answer, the Swiss army knife that came to solve two classic problems of post, either in advertising -my field- or in fiction.

The two problems

- Due to feedback from the client it is necessary to modify the editing of a sequence after all the effects work has already been done. This involves re-rendering, redistributing the new raw between compositors and managing versions of the same shot to compare before and after. A serious headache for all parties involved when retracing the path already taken.

- Ensure color continuity in the same sequence when there are shots that come from camera blanks and others are shots that have gone through compo (Chroma-keying, Roto, etc…) or are directly CGI. This implies that all the screens in the rig are calibrated equally, distribution of non-destructive LUTs so that compositors see green chromas instead of grays and also have a solid reference of the color of the sequence in which they have to integrate. A very complex color management pipeline that if it does not exist leads us to the eternal question of the chicken or the egg: is it better to color correct the shots before or after the compo?

The Swiss Army Knife Solution

AVID DS was a classic for the CONFORM/VFX/COLOR of the first films and series that made the leap to DIGITAL CINEMA and Davinci Resolve in its 16 version, in the fundamentals of its work philosophy and how it solves the 2 problems by integrating Fusion is basically its clone/unrecognized adopted son.

It is no coincidence that the first protocol for connecting Davinci to Fusion (the Fusion Connect option) is a modicación of Avid Connect, the script originally used to connect first the AVID DS and then the Media Composer to the compo program. It’s also logical that some of the most experienced disclosers of the Davinci-Fusion combination are former Avid DS users such as Igor Ridanovic.

Avid Ds and other applications that play the role of Swiss Army Knife (Autodesk Flame, Nuke Studio, Mystika) are known in the Anglo-Saxon industry as ̈Hero Suites ̈: expensive machines designed to play the role of heroic goalkeepers capable of stopping any ball that suddenly threatens the production and captaining the post department’s workow, always managed by operators who can solve any contingency by themselves, being good for both a broken and an unbroken, assuming different roles: editing, graphics, effects, sound, mastering (if you think about it, a bit like the tabs that are nowadays inside Davinci).

Avid Ds like Autodesk Smoke or many other programs that fit this Swiss model, disappeared due to a series of basic problems:

- The assemblers felt that the interface was too different from the one they were used to and that they had an unnecessary one, which is logical if we understand that it is not only for assembling.

- Being a very expensive seat at the time (around 70.000€ if memory serves me correctly), training places were almost non-existent, outside the accelerated course that came with the purchase of the machine, you could not count on tutorials on the internet compared to more modest applications such as Premiere or Vegas Video. -The aspiring operator had to learn in free hours in a friendly room through practice or meritoriaje, since he could not use it on his personal computer to practice at home and thereby acquire enough flight hours to earn a pilot’s license.

The current market

It is no coincidence that Adobe has not only increasingly connected Premiere and After Effects, but its editing program, after cannibalizing the Lumetri corrector from SpeedGrade, seems to incorporate more and more typical compo functions (masks, tracking, chromakeying) to make it easier for many users to avoid having to jump to After Effects, which seems to receive fewer updates in comparison.

This dynamic that is creating super-tools like Blender, which allows you to tackle 3D work as well as editing, VFX compositing or programming a video game. It is the same inertia that has led to Lustre being discontinued to become just another Autodesk Flame tool or what I believe is surely hindering the separation of SGO’s product categories (Mystika Ultimate -hero suite-, Mamba -VFX- and the recent Mystika Boutique -Lower cost Swiss Army knife).

The reason for this complexization of the tools: we are increasingly demanding to speed up the production of content, skipping the classic times and shifts between each phase of the post; the offline/online difference will definitely disappear, the time allotted for audio mixing, color and effects are increasingly compressed and disordered.

We need to do everything at once without tying our hands, there is no time for separate reviews of each department, and along the way we also want to eliminate the costs that could mean retracing the path we have already taken.

We need Hero-Suites for the poor….

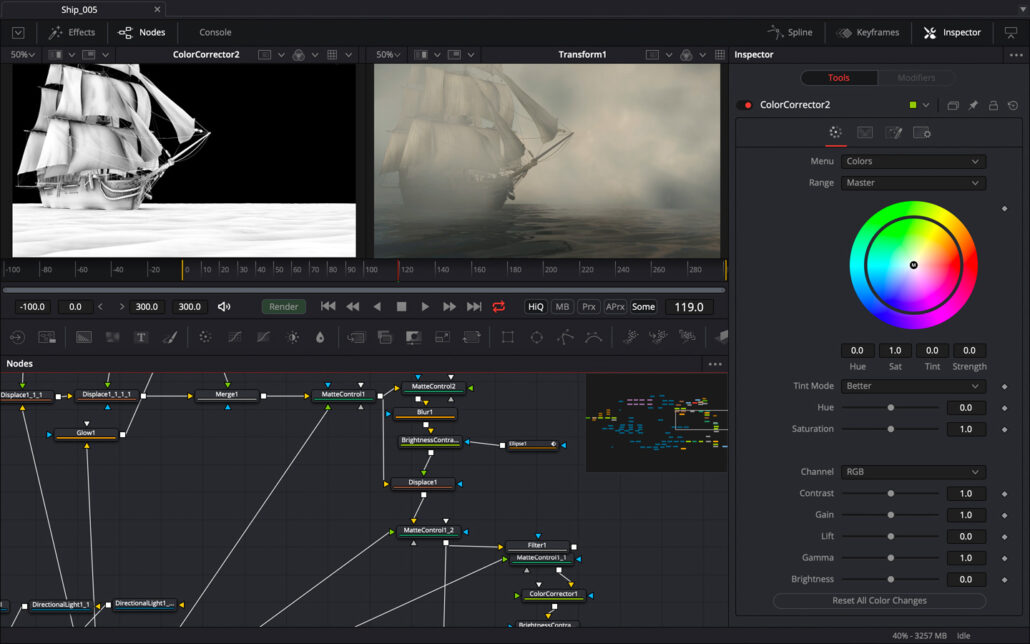

What is BMD’s solution to this market: Just take a look at BMD’s advertising and you will see that they are constantly emphasizing adjoining rooms where there are color, editing, effects and sound operators working IN PARALLEL all operating on a common Esperanto which is Davinci/Fusion. An old Hero-suite fractioned in different seats/ heroic operators each of them…..